Our Stories

Dr. Peter Yanada McKenzie

Bio - Dr. Peter Yanada McKenzie

PhD/Creative Arts, UWS. MA/Fine Arts, UNSW. Fulbright Scholar 1994 La Perouse Aboriginal Community Eora /Anaiwan

Indigenous Representative, Aboriginal Arts Advisor, Practising Visual Artist.

Dr. Peter Yanada McKenzie is a well known Aboriginal person from the historic La Perouse Aboriginal community in Sydney. He has had diverse experience as a practising artist, musician, project manager, university lecturer, Aboriginal ambassador overseas, arts grant recipient, researcher and Aboriginal committee member in several organisations.

His extensive area of experience in Aboriginal affairs covers Arts, History, Community affairs, Health and Education.

His artistic capabilities include commercial illustration, fine arts, music (drums, guitar,vocals), designer, guitar-maker (luthier), songwriter/singer, photography, sculptor/potter, writer, video- maker, and jewellery designer.

Dr. McKenzie curated What is Aboriginal Art? for the 2000 Olympic " Festival of the Dreaming" at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery, UNSW, and designed the National Logo for the Label of Authenticity for protection of Aboriginal cultural copyrights. He has also worked for the Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Museums Association of Australia as an Information and Public Relations Officer and Liaison Officer, respectively. He was Chairperson of the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative in 2000 and 2001 and Director of the Aboriginal Culture Centre in Armidale from October 2001 to April 2005.

Dr. McKenzie was granted a Commonwealth Department of Education Aboriginal Overseas Study Award, which enabled him to study photography, design, printmaking and commercial illustration at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, United States during 1982 and 1983. He was employed as Aboriginal Liaison Officer/Exhibitions Developer at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney in 1985 and later commenced work as an Aboriginal Liaison Officer/Project Coordinator with the New South Wales branch of Museums Australia in 1987. Dr. McKenzie participated as a Photographer in the After 200 Years project that same year, working with his own community of La Perouse.

in 1990 he was employed as a Project Officer/Aboriginal Programs at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney and curated an international Aboriginal art presentation (representing the Australian Government during the French Bi-Centenary celebrations) at the Centre George Pompidou in Paris for the major exhibition, "Magiciens de la Terre", in 1989.

Dr. McKenzie completed a Master of Fine Arts at the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales in 1993 and in1994. His photographic work was included in "Urban Focus: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art from the Urban Areas of Australia" at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra that same year. He has attained a Doctorate in Creative Arts at the University of Western Sydney in 2010. He is currently working in ceramics at his studio in Botany/Banksmeadow, Sydney.

Dr. Peter Yanada McKenzie uses the name "Yanada” as a mark of respect for his Sydney region forebears; the name means 'New Moon' and emanates from the Eora dialect of the Dharug Language in the Sydney region.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

By Peter Yanada McKenzie

It was sometimes bloody painful,...I knew I was 'different' as a kid, all my mates and relatives were black but alongside of them I was decidedly pale! In several old photos from the 'Dawn' magazine it showed I was a Koori kid wrapped up in white skin! I always felt a bit 'shamed that I was so "fair", but it didn't matter to anyone else at La Perouse! We had to grow up before the demeaning elements of racism would enter our lives. The background for my growing up was the historical Aboriginal mission at La Perouse, a suburb of Sydney, and in the last of the depression shacks of "Frog Hollow" which remained nearby.

Both my parents are Aboriginal and the only non-Aboriginal person in my family was a sailor, my English maternal grandfather; Harry James Cook, who, according to family history, migrated to Australia pre-WW1, by jumping off a Royal Navy ship, a sailor named James Cook who stayed in Australia, unlike his namesake!

The earliest memories of growing up was in Frog Hollow, situated between the Aboriginal Mission and the beach at Frenchman's Bay. It was a Depression village in the thirties which had never became unoccupied. Aboriginal people, poor white people poor black people and at the end of the second world war, dispossessed European refugees added to what could have been the first real multicultural community in Australia.

We had Koories, Maltese, Eastern Bloc countries, Polish, Hungarians, Russians, Balts, Greeks, White Russians, and even Gypsies, yes Gypsies! Alongside Frog Hollow was a state government home for orphan boys, a little regiment of boys marching up and down the other side of a fence that divided them from these dispossessed and unwanted refuse of "civilised" countries, which included Australia. However, we were all united by one aspect, everyone was in the same boat and it had a great big hole in it!

All of my mates were relatives or extended family and we enjoyed a childhood that more privileged kids could never imagine. We had four beautiful beaches, virgin bushland and a barefooted freedom to explore and make our simple lives; even with the bum out of our trousers, an Aussie kid's paradise.

Nicknames given to mates was a favourite Koori exercise and the brutal honesty was never questioned, all of us boys regaled ourselves with exotic nicknames like "Tarbaby", "Burnt log", "Bush Lawyer", it all depended on physical attributes and idiosyncrasies, naturally I was known mostly as "Macka”, no doubt suggesting forebears of an imaginary Scottish heritage.

At La Perouse in the 1950s there were travelling Aboriginal 'conventions' that used to take place on the Mission, they usually came from the north coast of N.S.W. and were of a severe evangelistic nature. Lots of threats of 'being taken by the devil' and people throwing themselves on the ground frothing at the mouth.

These participants were Aboriginal people, it was very weird for us kids to see adults rolling around on the ground frothing at the mouth wailing for forgiveness from their invisible God, who never seemed to have a tangible presence in the proceedings. We had resident white missionaries forcing religious education on us "little heathens" as they called us, these people had started a pastoral service to "soothe the dying pillow of the Aborigines" in the nineteenth century at La Perouse. Sunday school didn't cut any ice with "us boys", we religiously found adventures elsewhere!

We lived in several tin shacks in Frog Hollow until Mum, my young brother Davy and me moved onto the mission to live with our Aunty Ollie Simms, leaving the little blue twelve foot square dirt floor shack Uncle Bob had built for us on the hill overlooking Botany Bay, Randwick council then tore it down. Mum and my father had finally parted, she finally threw in the towel after years of unsupported survival.

Mum struggled to keep Davy and me alive in some reasonable fashion by working at the hospital as a ward's maid, a kitchen hand at the NSW golf club at La Perouse, many other servile and menial jobs. Mum did the best she could for us, our Aunty Ollie was very supportive. Aunty was very close to Mum, she was a stern old lady and wasn't prone to showing affection, but she took us in her care when the chips were down. Aunty was my Grandmother's sister, we all loved her dearly.

Oddly enough most people were wary of her!

Living on the mission with Aunty Ollie was an unexpected luxury, even if we did not have electricity, the house had an outside communal toilet and a single coldwater tap on the veranda. There was no such thing as a kitchen sink or bathroom and our kitchen fuel stove ran on wood and coal, the smell of burning wood and tar has memories for me, my job was to cut up the wooden road blocks the "Wood-O” delivered for the stove. Aunty Ollie and my young cousin Greg had one room and we had the other. Mum and Davy slept in the bed and I slept on the floor.

At least it didn't leak and it was warmer than the shacks, I had been in a convalescent hospital at Camden after getting pleurisy and pneumonia from living in the draughty tin shack. Our cousin Jessie occupied a small sleepout on the veranda of Aunty Ollie's house, she was the daughter of Mum's cousin Gladys, we were all very close relatives and for once we were all a happy little family.

Although those non-electric and asbestos ridden mission dwellings were the norm, we were only one tram ride from the Sydney harbour bridge! The kitchen had a dresser, a table and chairs, a cupboard food 'safe') a cast iron fuel stove with an oven, we also had a top loading ice chest. We used a kerosene lamp at night or candles. The house was one of the houses built on the 'new' mission of 1928, after the old tin shack mission was revoked and the new mission gazetted up to the new site.

These houses were by description, a timber frame and wooden floor, the asbestos wall linings were fastened to the inside of the frame and the roof was corrugated asbestos, they were known as the 'inside-out' houses, because of the skeleton like appearance. I went on to high school from this house and failed miserably in everything I attempted to do, homework was impossible, I hated school and I even had to wear shoes and a tie, this new regimentation was not for me, but Mum worked hard just to keep me there.

I often reflect that this period in growing up in Australia on a mission in the middle of Australia's biggest city, was really quite primitive, we were still under control of mission managers who were despotic failed public servants and missionaries who were patronising do-gooders. I often wondered what they eventually did with their lives after they lost 'control' of us 'Heathens'.

One of the major events we experienced in the life of a kid growing up at La Perouse was the Mullet seasons, net fishing off the beach was Sea of Galilee style, a net was dropped overboard by rowing the skiff around the school of fish and it was 'hauled' onto the beach from both ends until the net full of fish was on the beach. If it was a large catch, a lot of people, especially us kids! were required to haul the net in. Sometimes fish would jump out of the net in panic, they were the lucky ones! because every other fish was destined for a coat of plain flour, fried golden in beef dripping and washed down with strong black tea, usually accompanied by 'johnny cakes'. Fat and flour!, this terrible unhealthy dietary combination was hopefully, balanced by the omega content in the oily mullet!

There was one group of men on the mission us kids avoided at all costs, we were savvy enough to know that we could end up the same if we were not smart enough to steer clear of them, we couldn't really avoid them, they were our fathers and uncles.

I am referring to a sub culture of bludgers and drunks who are seen as 'good ol' fullas. These rejects were not the sadly dispossessed of traditional culture whose purpose was supposed to provide for their own, these were the low lifes whose mission in life was to drink with their fellow travellers ('the boys') as often as possible and to avoid at all costs some form of regular employment or responsibility.

But at home it was another story, the 'mates' don't have to listen to the abuse, take the mental and physical punishment that their 'brothers' dealt out at home, indeed when informed of same there's always an excuse in favour of the villain. “Oh she's a bloody nagger"; "the kid deserves a slap under the bloody ear'ole"; "e needs a bloody good kick up the arse!" These men (the so called brothers) saw each other as a sort of matey club, a group free of responsibility.

When my father got a couple of days work it would be later spent on drinking with his mates, he would come home to the shack late at night with a couple of bottles of beer and scraps of food. Scraps that he would buy at the ham and beef shop (delicatessen) at Matraville, a couple of shillings worth of end pieces and scraps of devon, garlic, half a pigs head and exotic stuff like salami, but only the disgusting end scraps. He would be drunk and his solo partying would continue through the night. He wouldn't let us go to sleep, just as Mum or I would be nodding off he'd poke at us and wake us up again. I guess it was a sort of instinctive sleep deprivation torture on his part.

I lived in constant fear of being backhanded for even looking sideways at him, a sort of state of constant nervousness whenever he was around. I used to wish that I could some how be 'saved', I always thought that it was a terrible mistake and that he was not my father and that one day I would be taken away by my real father whoever that was, I never once in my life ever called him Dad.

He was a coward who constantly hit me and threatened Mum. His big threat that he would punch her in the breasts, when I was eventually old enough to flog the bastard, I was cheated out of it, the grog had him so bad that it killed him. To this day I have never got over the injustice of that denial...I think of it as my little bag of rocks.

The next day my Mother still had to get up early and go to work, sleep or no sleep and I still had to go to school. Curiously enough I was an excellent student at primary school, always in the top three students in exams and it wasn't until I went to high school that my education and desire for learning came to a full stop. It was there that I had my first bitter taste of racism, again I had experiences that I never could repeat or understand, and why didn't anyone protect me?

I jumped over the school fence the day I turned fifteen, vowing never to set foot in a schoolyard ever again, I was finished with an education system that couldn't teach me anything or even give me a little respect for my culture, I decided that it was up to me plot my own course.

So I left behind the beaches and bushland of my childhood at La Perouse. However, not a day passes when I am not reminded of who I am, and how proud I am,....of where I came from...

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The writings above remain the copyright of Peter Yanada McKenzie and are reproduced here with his kind permission.

Where I Came From

Tim Blake

Yanada: The Story So Far

by Tim Blake

(told as briefly as possible)

Back in England, in school, I’d been good at art and metalwork and managed to get into a five year apprenticeship learning how to make handmade upmarket jewellery. That all went well, but along the way I’d gotten the travel bug. Even after back-packing with an Australian girl around Greece, Israel, and Egypt I still wasn’t quite satisfied. So I sold my Triumph motorbike to raise the fare to Sydney to meet back up with her, arriving December 1982.

The six month work permit was eventually changed to permanent residency. For a few years I was working as a sales assistant selling jewellery in shops, then there was a couple of years driving a taxi, then I found myself back at the bench working for a company that produced and sold jewellery at a wholesale level. After a few months there, I felt that I could do it better myself, so took a leap of faith and in January 1989 sat down to design and make my own range to sell to shops. Thankfully, the jewellery trade liked ‘my stuff’ and the business grew.

At the end of 1992, there was a new Jewellery Trade fair at Darling Harbour. I displayed my jewellery there, but kept down the cost by sharing a booth with another sole trader. The Fair was run by the Jewellers Association of Australia, and in conjunction with it, they were also running a Design Award Competition. Not being able to afford lots of gold and diamonds, I went in the category that was cheapest to enter, and amazingly, I won the Manufacturers’ Design Award.

While at that Trade Fair, I was dismayed at seeing how many manufacturers were trying to cash in on the tourism dollar by directly ripping-off Aboriginal art, or making up their own ‘Aboriginal style’ designs and putting them into jewellery.

I remember thinking at the time, and then saying to my wife “How hard can it be to find an Aboriginal artist to work with?”

Well it didn’t turn out to be hard at all. Looking back, I am so grateful for the wonderful experience and strong friendship that the small effort turned into.

I looked in the telephone directory and found AAMA, which stood for Aboriginal Arts Management Association. It was a Federal Government funded organisation that was formed to protect the work of indigenous artists. Their office was in Surry Hills, and I visited them there one day and told them what I hoped to achieve. Apparently, my request was unusual so they weren’t prepared, but they said to leave it with them and they’d ask around.

Within a couple of days, I got a call from an Aboriginal artist named Peter McKenzie who told me that AAMA had passed on my number. I told him about myself, and my hope that I could work with an artist and make jewellery that truly was of Aboriginal design. Peter had a great interest in all forms of artistic creativity, and had already wondered about making jewellery. Plus, he told me, it was the ‘International Year for the Worlds Indigenous Peoples’ so in the spirit of harmony, he thought we should give it a try.

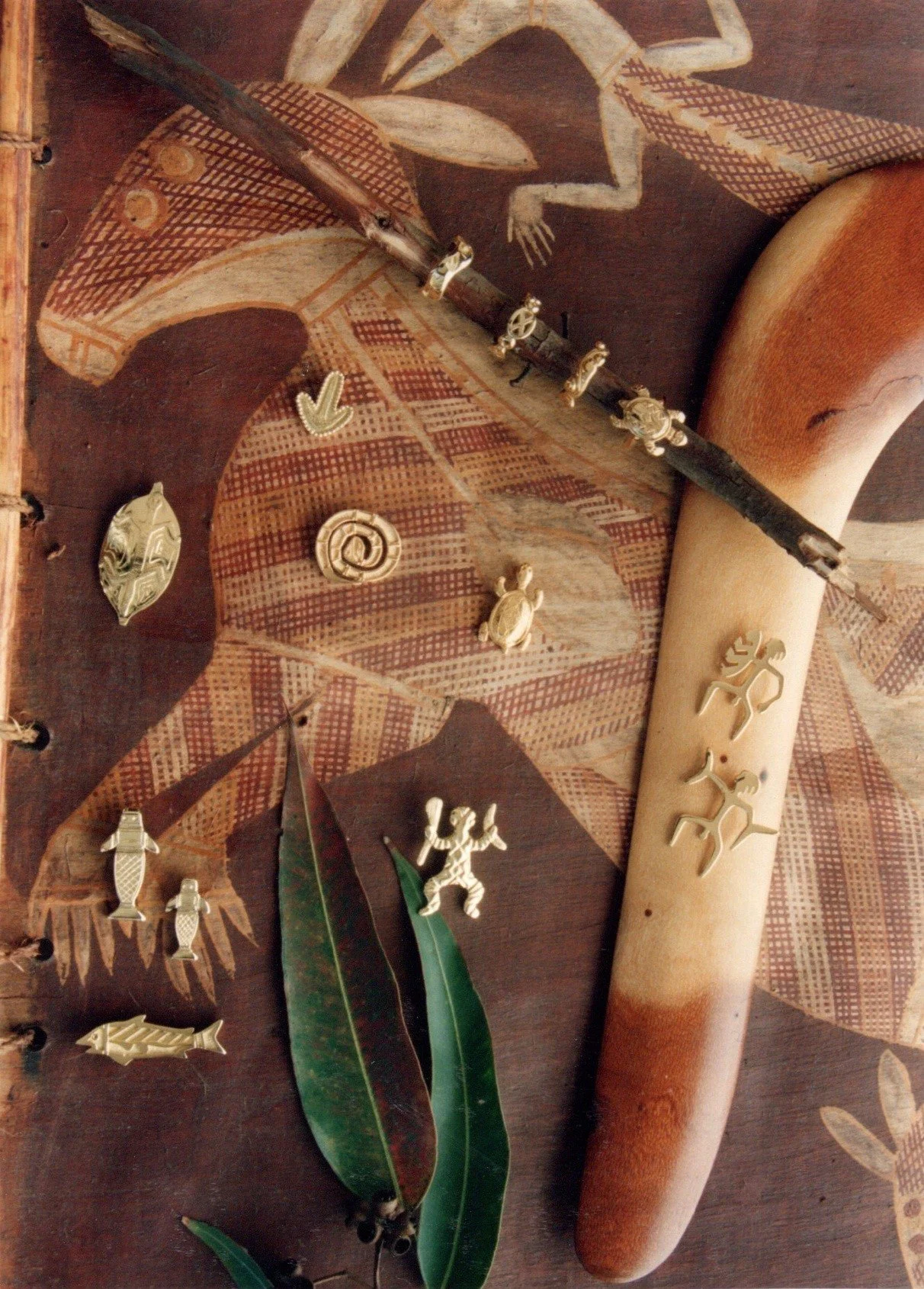

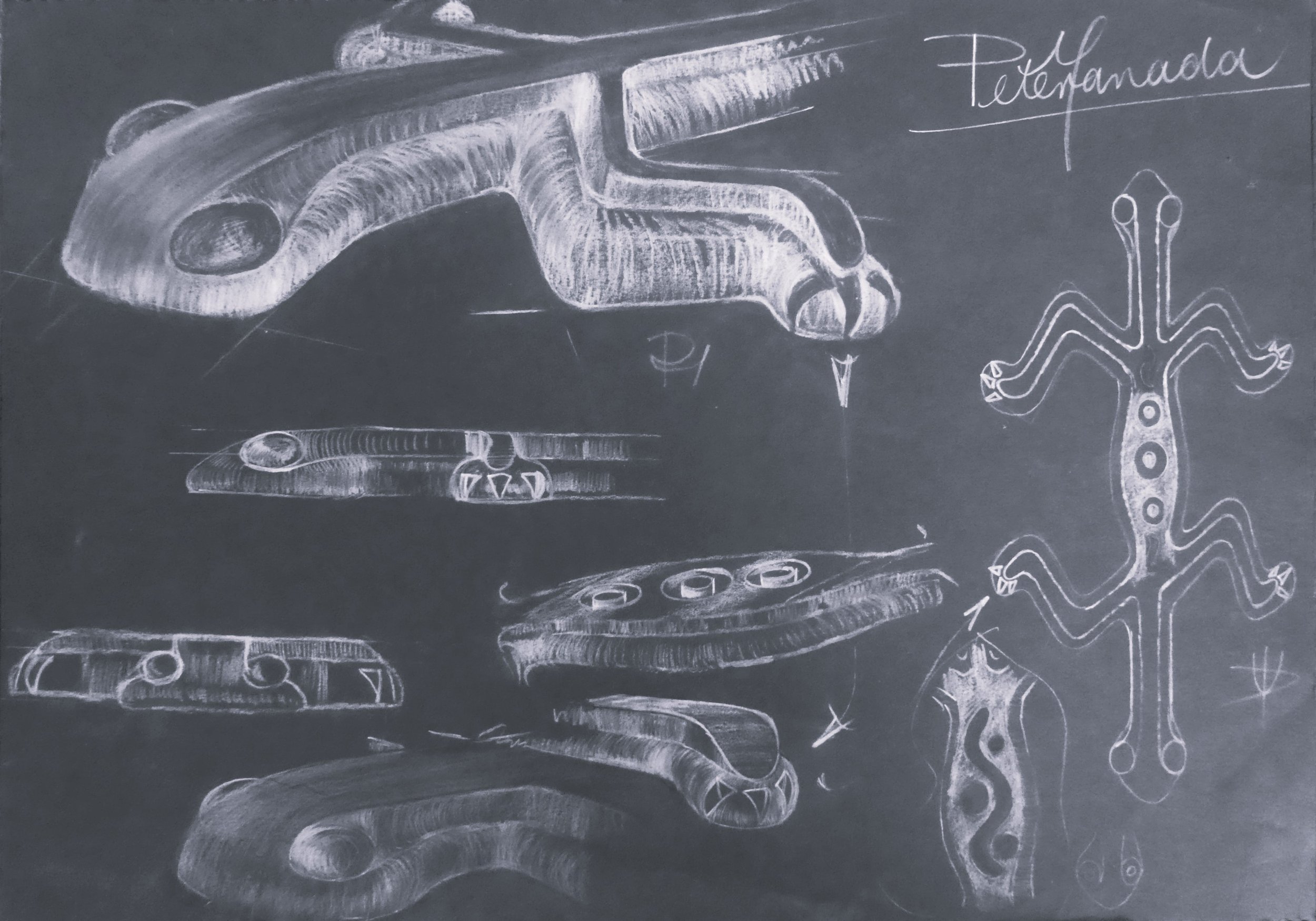

At that time, I worked from home in a rented two bedroom plus sunroom house with a single garage. My bench was in the tiny sunroom, my desk in the bedroom, and the dirty dusty polishing equipment in the garage. So when Peter came over, we worked at the dinner table. I showed him my jewellery and explained the different processes that could be used to make it. He already seemed to have quite a clear idea of the style he wanted to try, which was taken from ancient Aboriginal rock art, and traditional patterns and motifs found on artefacts.

Oh my goodness. From the moment Peter started drawing I knew he had a genius talent. Watching him conjure images with a pencil on paper was for me, quite a spiritual experience. I still wonder at his modesty. I know he’ll be embarrassed when he reads this; hopefully not too much.

So full steam ahead, and it wasn’t long before we had a range of Aboriginal designs in jewellery as well as a little certificate of authenticity for each piece. Along the way, Peter had the idea of calling the collection Yanada, being a local language word meaning new moon or new beginning. He felt this summed up his feeling that the project had its roots in a new start for reconciliation, collaboration, and harmony. Peter felt so strongly about this, that he made Yanada a part of his name and became Peter Yanada McKenzie.

Then it was my job to sell the Yanada Collection. We had a stall every Saturday at Paddington Market (started by my wife and her sister) where they sold my gold jewellery. We put Yanada in there, and it did quite well selling direct to the public. It was the right atmosphere and a good mix of customers from inner city Sydney, interstate visitors, and international tourists. But selling it to jewellery trade customers to put in their shops proved to be a completely different, and eye-opening experience. Amongst the individually owned independent shops, some would commend me on my efforts but would not buy, while a very few bought perhaps one piece for their own private collection. When it came to the much larger businesses with multiple shops that were the backbone of my business and income, well.. the reactions were blunt, angry, threatening, and racist beyond any doubt. The further from Sydney I went, the more shocking the comments became.

Although Yanada wasn’t going to sell to most of the mainstream outlets, we still had a following through Paddington Market and that stopped us from being too disheartened.

There was another design award competition coming up, and it included the category of ‘Tourism Design Award’. I expected the usual rip-off guys would probably enter their bogus things. Perhaps I was a bit cranky, or maybe just had a touch of madness, but I definitely wanted to stir things up. So I asked if Peter would come up with an idea for a big statement piece of Aboriginal designed jewellery, something ‘major’ that would be entered under his name as the designer. I couldn’t see how it wouldn’t win and be splashed all over the fashion magazines. At the very least, it would be a finalist and get some publicity.

Peter’s genius and diligence produced a design for a large necklace and earrings to go with it. The necklace was made in 18ct yellow and white gold and was formed from long and short curved echidna quills; then as a centrepiece there was a ceremonial stone-bladed dagger. The blade was cut from a piece of beautiful boulder opal, specially shaped to appear as if the opal had been ‘flaked’ to a knife edge in the traditional way.

I put 100 hours of labour into this piece. On top of that, other craftspeople, including the man that cut the opal knife and earring stones, also did their finest work. I didn’t count the cost. Priceless, unique, and well worth all of the effort.

I contacted TNT Failsafe, the preferred courier for the Jewellery Design Awards, and they picked up my package to take it to Canberra for the judging.

I was contacted the next day to be informed that the TNT base at Mascot had been robbed by men armed with machine guns. They were after some engraved plates used to print banknotes. They got them, and everything else.

We were out that night for dinner in a restaurant in Leichhardt when grief overtook me, and I spent most of the meal crying uncontrollably into my napkin.

A day or two later, there was a knock on the door and two officers from CIB (Criminal Investigation Bureau) showed me their badges. They thought that I might’ve had something to do with the robbery; hadn’t actually sent the goods, and was trying to pull an insurance scam. Yeah well, I didn’t have any insurance and the TNT smallprint basically said they were a ‘common carrier’ and all care but no responsibility. I don’t think we even got a refund on the courier charge. As they were leaving, I asked them if they had any leads and when could I expect the necklace back? The Police report tells me the robbery took place on July 4th 1994. To date, I still haven’t heard anything.

What with all of that having happened, I think the wind was taken out of my sails. As well, we were expecting a new baby in a few weeks so I must have gotten a bit distracted. The Yanada Collection went on the back burner, but Peter and I stayed in touch. Over the years he’s been bestowed with many accolades for his work, and some letters before and after his name. I continued to make jewellery, but never entered another jewellery design competition.

Getting on for thirty years later, once or twice I’d asked my son if he was interested in doing something ‘online’ with my old wholesale range of jewellery, but that idea didn’t grab him at all.

Then I remembered that ‘Yanada’ had all happened before he was born. So although Harry knew about Peter, he’d never really heard about the jewellery and it’s history. I showed him the ‘masters’ and Peter’s drawings, the little certificates, and told him the story. This time Harry was enthusiastic and could see that this was a worthwhile and meaningful project that deserves to be given a new lease of life.

We went to see Peter who said he would be happy if Yanada was re-launched. It has all taken much longer than it did originally. Mostly due to the fact that I’m not quite as energetic as I used to be, and these days there’s more legal hoops to jump through. Back in the day we just went ahead and got on with it, but now, we must be able to show that everything has been done above board and with the artists best interests at heart. So it’s all been signed and sealed with Harry now holding the Licence to use the Yanada designs from the Copyright which Peter owns.

So here we go again, and I’m glad that this time we have the internet as a tool to find the people who will appreciate the art, the history, and the hope for harmony.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Some more photos from 1994 ‘back in the day’:

Yanada

The Collection

Tim